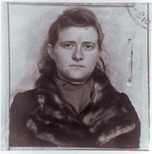

Tosia Altman grew up in a Jewish Community in Lipno, Poland. She learned Polish and Hebrew and was an active member of the Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir youth movement. With the outbreak of World War 2, she became a spy for Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir. A fearless leader in the Jewish clandestine resistance to the Nazi occupation, Altman played an integral role in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of April 18, 1943. She was badly injured in a fire in the attic in which she was hiding. Altman died a few months later in the custody of the Germans.

The leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir in Vilna was extremely concerned with the fate of the movement’s members who were left behind under German occupation. As a member of the central leadership, and with the appropriate personality and appearance, Altman was instructed to return to the Generalgouvernement (Nazi-occupied Poland). She was the first to return to occupied Poland (followed later by Josef Kaplan, Mordecai Anielewicz and Samuel Braslav).

After two failed attempts to cross both the Soviet and German borders, she finally succeeded. Altman gathered the remaining youth-group leaders and organized the movement’s branches. Even though Jews were prohibited from traveling on trains, Altman began to make the rounds of other cities. In every city she reached, she encouraged the young people to engage in clandestine educational and social activity. Altman corresponded with the leadership in Vienna (Adam Rand), the movement in Palestine and emissaries in Switzerland (Nathan Schwalb and Heine Borenstein). The correspondence was written in code for fear of German censors.